History tells us there will be plenty of gems to be found

Date:

This article originally appeared in Racing Post .

In 1983, a Nijinsky half-brother to Triple Crown winner and then new hot sire Seattle Slew, who would become Seattle Dancer, set a world record for a yearling thoroughbred sold at public auction, for $13.1 million – a record that still stands.

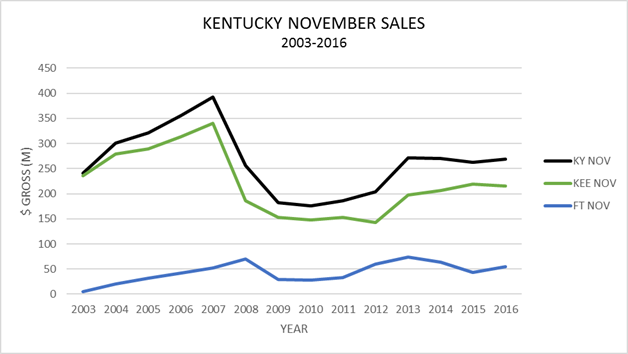

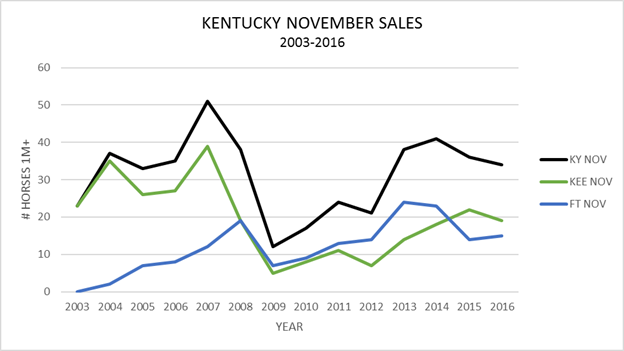

At that time 80 per cent of the top stallions stood in North America. Three years later, in 1986, a deep recession took hold of the thoroughbred industry on both sides of the Atlantic that lasted until 1992. It took until 1995 until the green shoots of recovery took hold. That boom lasted, in the thoroughbred industry, until mid-2008 when the world economic collapse took the thoroughbred market down with it, as the accompanying tables show.

At that time 80 per cent of the top stallions stood in North America. Three years later, in 1986, a deep recession took hold of the thoroughbred industry on both sides of the Atlantic that lasted until 1992. It took until 1995 until the green shoots of recovery took hold. That boom lasted, in the thoroughbred industry, until mid-2008 when the world economic collapse took the thoroughbred market down with it, as the accompanying tables show.

The current recovery began in 2013, and prices have materially advanced at this year’s yearling sales for the first time since.

Well before the 1986-92 recession, new Arab interests including the Maktoum family and Prince Khalid Abdullah began acquiring top American stock, and during the recession Japanese interests, mainly the Yoshida family, also began acquiring top American bloodstock, including Sunday Silence. At the same time Sadler’s Wells, at Coolmore, was re-establishing the European stallion market so successfully that by the mid-2000s the balance of top stallions was back to 50-50 between Europe and North America.

Kentucky November Sales 2013-2016 (not including dispersals)

Deprecated: auto_detect_line_endings is deprecated in /var/www/vhosts/des-dev.xyz/httpdocs/columns/20171013-0001.php on line 48

| Year | Kee Sold | Gross | 1m+ | Kee% Gross | Sold | Gross | 1m+ | FTK% Gross | KY Nov Sold | Gross | Average | 1m+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2,614 | 236,070,900 | 23 | 98% | 59 | 5,160,000 | 0 | 2% | 2,673 | 241,230,900 | 90,247 | 23 |

| 2004 | 2,873 | 279,680,200 | 35 | 93% | 201 | 20,685,800 | 2 | 7% | 3,074 | 300,366,000 | 98,783 | 37 |

| 2005 | 2,816 | 289,602,900 | 26 | 90% | 112 | 32,183,000 | 7 | 10% | 2,928 | 321,789,500 | 109,900 | 33 |

| 2006 | 3,147 | 313,843,800 | 27 | 88% | 99 | 42,353,000 | 8 | 12% | 3,246 | 356,196,800 | 109,734 | 35 |

| 2007 | 3,381 | 340,877,200 | 39 | 87% | 107 | 52,036,000 | 12 | 13% | 3,488 | 392,913,200 | 112,647 | 51 |

| 2008 | 3,019 | 185,552,300 | 19 | 73% | 91 | 70,279,000 | 19 | 27% | 3,110 | 255,831,300 | 82,260 | 38 |

| 2009 | 2,779 | 152,727,800 | 5 | 84% | 80 | 28,905,000 | 7 | 16% | 2,859 | 181,632,800 | 63,530 | 12 |

| 2010 | 2,929 | 147,392,900 | 8 | 84% | 89 | 27,996,500 | 9 | 16% | 3,018 | 175,389,400 | 58,114 | 17 |

| 2011 | 2,384 | 152,691,200 | 11 | 82% | 79 | 32,745,000 | 13 | 18% | 2,463 | 185,436,200 | 75,288 | 24 |

| 2012 | 2,414 | 143,025,600 | 7 | 70% | 87 | 60,220,000 | 14 | 30% | 2,501 | 203,245,600 | 81,265 | 21 |

| 2013 | 2,457 | 197,189,000 | 14 | 73% | 129 | 73,859,000 | 24 | 27% | 2,586 | 271,048,000 | 104,813 | 38 |

| 2014 | 2,512 | 205,899,500 | 18 | 76% | 108 | 63,678,000 | 23 | 24% | 2,620 | 269,577,500 | 102,892 | 41 |

| 2015 | 2,575 | 218,959,400 | 22 | 83% | 92 | 43,666,000 | 14 | 17% | 2,667 | 262,625,400 | 98,472 | 36 |

| 2016 | 2,653 | 215,213,000 | 19 | 80% | 88 | 54,152,000 | 15 | 20% | 2,741 | 269,365,000 | 98,272 | 34 |

| 2006 | 71 | 21,777,000 | 6 | 2006 | Classic Star Dispersal | |||||||

| 2011 | 170 | 55,820,000 | 12 | 2011 | EP Evans Dispersal | |||||||

Over the past 20 years, American pedigrees have become increasingly hard for Europeans to understand and that, coupled with the emergence of viable stallions and a thriving marketplace in Europe – exacerbated by the perception of American racing as drug-ridden – means that European buyers are not so sure any more what they are looking at in American sales catalogues.

What has become increasingly clear, though, is that even though American breeders have exported many of their formerly recognisable names, North America still continues to produce world-class horses – they just don’t have pedigrees many international buyers recognise.

Big problem, of course, but it does not alter the fact that North America and Europe are still by far the two biggest consistent sources of top-quality racehorses. It seems that no amount of export or drugs have caused America to become anything other than a true world-class producer of top thoroughbreds.

The continuing success of North American-bred horses on the racecourses of Europe, especially in light of the small numbers exported for racing there, is impressive testimony to this.

Part of the reason for this continuing success is the sheer size of the American marketplace. Even at its lowest ebb there were never fewer than 2,500 horses sold for less than $175m at the November Fasig-Tipton sales.

Normally the North American market in general is twice the size of the British, Irish and French markets combined. But the other reason has to do with that intangible but crucial variable we call ‘class’.

Since the 2013 recovery no fewer than 34 hourses have brought final bids of $1m or more at the Kentucky November sales, and that is not because people have money to throw around: it is because buyers understand that vast cauldron of American dirt racing (and now, increasingly, a welcome surge in grass racing) continues to produce world-class racehorses, broodmares and stallion prospects – even if the pedigrees are harder to understand.

Even as the horse, and all other markets, were collapsing around us there was a major revival in the American stallion ranks. The first foals by a ‘fearsome foursome’ who all rapidly shot into the top ten sires – Tapit (Gainesway), Medaglia D’Oro (Hill ‘n’ Dale, Stonewall, then Darley), Speightstown (WinStar), and Candy Ride (Hill ‘n’ Dale, then Lane’s End) – hit the racetracks in 2008. Kitten’s Joy’s (Ramsey Farm, now Hill ‘n’ Dale) first foals ran in 2009, the same year Sea The Stars rewrote the record books as a three-year-old in Europe.

The first foals by War Front (Claiborne) raced in 2010. Curlin (Lane’s End, then Hill n’ Dale) and the surprise package Into Mischief (Spendthrift) had their first foals appear in 2012, the year Frankel concluded his own record-breaking career, followed by new top sires Pioneerof The Nile (Winstar) in 2013, the year the horse market started to recover, Quality Road (Lane’s End) in 2014, the sensational Uncle Mo (Ashford) in 2015, and Union Rags (Lane’s End) in 2016. America has produced some seriously important sires in the last ten years and will continue to do so.

A couple of tips about the logistics of the Kentucky November sales. Fasig-Tipton will kick off proceedings on Monday afternoon (Sunday is a travel day when the Breeders’ Cup is in California) with a one-day sale, weanlings first, then mares and fillies that will include several multi-million dollar offerings, such as Tepin and Songbird.

Keeneland Book 1, including another superstar in Lady Eli, gets under way on the Tuesday; at Keeneland the foals and breeding stock are intermingled, rather than separated as in Europe or at Fasig-Tipton. One highlight is sure to be the first foals by American Pharoah (Ashford), in 2015 the first American Triple Crown winner in 37 years. He is represented by six weanlings at Fasig-Tipton and another 22 at Keeneland.

One other thing is an absolute certainty – as American racing and breeding have proved over and over again, even with pedigrees that are harder to understand and a foal crop 40 per cent smaller than it was ten years ago – there are going to be plenty of world-class broodmares, broodmare prospects and foals who will come out of these sales. That much, history assures us, is guaranteed.